Garden of Earthly Delights

Garden of Earthly Delights

The bountiful forests of Southeastern Australia

The dawn is hours away in a bountiful, shady forest, and it's finer creatures start to stirr. One would expect to see martens, foxes and squirrels among the branches of such a quaint, dappled forest, but 25 million years from now, things are different.

Gone are the days of Australia's placental predators, the feral cats, dingoes and foxes are long gone. In the ice ages at the start of the neocene, bass strait opened and closed as the ice ages dropped the sea levels, and the interglacials raised them. Tasmania, a bastion for marsuipial predators since the holocene, was again, as in ice ages past, linked to the mainland. The Marsuipial predators mixed with the placental predators of the mainland, numerous times before the ice ages finished. This flurry of colinisation and competition tempered the fires of the evolutionary furnace, and the marsuipial predators, with a higer rate of reproduction, competed sucessfully with the carnivorans. At the close of the last ice age, waves of rabies and kennel cough epidemics swept meganesia, decimating the placental predators. It was at this point that the marsuipials took back what was theirs, and became top predators once more.

The trees in this forest are an odd mix, native wattles and eucalypts share the canopy with pine trees introduced by man, while the middlestory is a milange of introduced fruit bearing trees, plum, peach, citrus and olive. These trees florished in the holocene as introduced weeds, and as Australia's seasonal southeast moved north in the neocene's continental drift, it beacame became a wooded garden paradise. These woods start in eastern-south-australia, merging at it's northern fringes with the treed savannas of the once arid centre. To the east it spreads through most of Victoria, up into the blue mountains of New south Wales and down to old sydney harbour, where, as one goes north, it merges with the subtropical woods that lead into the tropics. Glory and grape vines string between the fruiting trees, moss and lichen cover the branches, fertilised by falling guano, fruit, and water from above. On the forest floor, enough light gets through for a carpet of ferns, herbs and orchids to grow in patches among the leaf litter, many of which have large roots and tubers to help store nutrients for harder times.

The Towering eucaypts, constantly dropping branches, continually open up new patches of light for the bushy trees below, but here in the treetops, one would be mistaken for thinking that you were in asia. Grey-black, round headed mammals swing through the trees, chewing on eucalyptus leaves, gumnuts, bark, and fruit. This creature, much like a gibbon in size and shape, but also having a medium-length tail, is actually descended from the Common Ringtail Possum (Pseudocheirus peregrinus), a creature that also gave rise to the marsuipial lemurs. Athletic and long limbed, this so-called Ape-possum (Pithecopetaurus hylobatoides) is only slightly like it's ancestor, they swing on long arms through the branches, roar like stags to reinforce social bonds and claim territory. Their digestive systems can process eucalyp leaves and other foliage, which is their main food, very well, and they often also eat fruits and nuts for energy. When they leap between trees, it is their powerfull limbs that provide the propulsion. Though they are ape-like, their brains are only slightly larger than their ancestor because they live in family groups. The real neurological advantage the marsuipial apes have, as do macropods, is an independantly evolved nerve link between the brain's two hemispheres, which allows better coordination and improved agility. This feature, though standard for placentals, has had to evolve independantly in marsuipials.

The eucalypt gecko (Eucalyptogekko ledii)

Is a ten centimeter, diurnal, eucalypt dwelling, insectivorous gecko. It has a body that is almost identical in patterning, shape and colour to a eucalypt leaf, and is usually very hard for a predator to find in the canopy.

The pines harbour Black-green Pine cockatoos (Pinocacatua chlorocaudus), descendants of Red-tailed black cockatoos. These noisy, messy, smelly, winged brutes eat pinecones, pine nuts, pine needles, branches and constantly drink the poisonous pine sap. They process the sap and incorporate it into their tissues, refining the poison and storing it in glands under the tongue. When a predator comes along, they open their mouth and spray the foe with noxious, sticky fluid, allowing the birds to escape.

Occasionally, a cockatoo will screech and reel back from the cone it was eating, having been bitten by an tiny foe. The Pine-Pseudoscorpion (Arboropseudoscorpios pinophagus), is an inch long, bright red, and has poisonous mouthparts and pincers, unlike their ancestors. They raise their young in an open pinecone, also protecting fiercely the cone itself, untill the eggs hatch. Then they vacate the cone and allow it to fall, on the forest floor, where the young grow to maturity on the insects of the leaf litter.The adults will find a new nursery next year. The adults feed mainly on insects and spiders in tree bark and pine needles, never straying more than ten metres from their home cone.

The Pine gecko (Pinogekko chloris) is a twenty centimetre long, bright green, insectivorous gecko, being crepuscular and dwelling among the pine needles. The creature is covered almost entirely with long, green, quill like scales which look very much like pine needles, allowing it to blend in perfectly with it's habitat among the pine needles.

-

Rat-sized Red fox-bats (Pteropodoides frugophilus) can be seen everywhere among the fruit and leaves. A descendant of the little red flying fox, this crepuscular species gorges on the bountiful fruits in the forests that cover Meganesia's southeast.

Swooping violently, with a disturbing, warbling war-cry is the hawk-currowong (Mortavis mordax). Chocolate brown, with a blue sheen to it's feathers, and a two metre wingspan, it crashes down into lower brances to grab prey with it's curved talons and meat-cleaver beak. It is descended from the large, omnivorous, magpie like bird called the Currowong, and, in the abscence of eagles and hawks, it is one of the top aerial predators. As it sits on a branch, with a bat pinned under it's talons, it rips at it with it's hooked, black beak.

Down among the fruit trees, false-marsuipial lemurs (Pithecotricosurus papiops), descened from the common brushtail possum, growl and hoot as they gorge on fruit, they leap and chatter like some otherworldly, ten kilogram, brobdignagian squirrels. Their faces are bright blue and leathery, with huge incisors, and yellow stripes on the cheeks. Their fawn coloured fur is thick and wooly, the males have an orange and brown-red tail to attract females in the mating season, which lasts for most of the year. True marsuipial lemurs are mostly descendants of the Common Ringtail Possum (Pseudocheirus peregrinus), but this beast, a false-marsuipial lemur, is descended from the larger and more agressive brush tailed possum.

The false-marsupial lemurs mob a large, surly, branch-clambering monitor, one that would very much like to eat their young. The tatoo monitor (Frugovaranus lydiai) is a large, mossy coloured monitor, with thick, knobbly green scales that fray into moss like filaments at the edges, and is crossed with tracing patterns of pink and yellow, like the lichen that grows among the moss. Though cryptic, this monitor, fifty centimetres broad, and two metres long, it's diet is mainly small mammals, amphibians, and birds. It can sit for days, digesting a gorged meal , going practically unnoticed due to it's cryptic markings, these markings also allow it to sit in wait to ambush prey. The markings resemble tatoos, hence the name, in referance to maori tribal tatoos.

Another, more lengthy, but equally dangerous reptile, with long toes and an incredibly long tail, the scarlet tree dragon (Toxicagama longus), clambers lazily towards a bunch of fruit. Far from being cryptically coloured, it has bright red and black banding, and a large, round head, and it's gular pouch is bright blue. It's a descendant of the Water dragon, an agamid that inhabited eastern australian forests and rivers, it has since left the water behind, and taken entirely to the trees. A large, unarmored, tree-dwelling lizard would be an easy meal for a predatory bird or mammal. But an old, and almost unknown attribute of agamids, undiscovered untill the early twenty first century, is their mildly venomous bite. In the neocene, the scarlet tree dragon is extremely venomous, and can subdue an over-inquisitive false-marsuipial lemur with a single bite, which makes the bitten animal extremely sick, but this is only for the creature's defence, all the dragon eats is fruit.

The trees are suddenly alive with large, gaudy, red, black and blue birds, with white-yellow facial markings, fruit eating crows (Frugocorvus viridus). These birds eat fruit and insects constantly, cawing loudly and waving their thick, yellow bills at each other. Double the size of a modern crow or raven, they have a large stomach for digesting fruit.

Fox sized, Red tree wallabies (Arborowallabia agilis) zip past in the clamour, just as agile as their rock-wallaby ancestors. Leaf and fruit eaters, they constantly move through the undergrowth, chirring and waving their brown-red, fluffy tails. Their young grow quickly, and are out of the pouch within two weeks able to speed through the trees with their parents.

Once the chaos of fur and feathers pass, the branches and ground below are strewn with partly eaten vegetation, fruit, dung, and urea. The herbivores are easy for the resident predator, the Marsuipial civet (Phascolocivetta australiensis), to track. Eating mainly animal matter, but also olives, grapes, and flowers, their family groups can bring down marsuipial lemurs with ease. The males mainly wander alone once they mature. This creature, like other neocene marsuipial predators, is descended from marsuipial mice, small dasyurids.

Enough to make even the most headstrong marsuipial-civet-bachelor run away like a mouse is a large, fierce possum. The marsuipial jaguar (Phalangerobalam ferox) , a semi-arboreal, sixty kilogram, carnivorous possum. With huge, razor sharp claws, gripping thumbs on feet and hands, and wide jaws with huge hide piercing incisors, and slicing molars, it can make short work of even a bear-sized-marsuipial. It's fur is grey-fawn with black stripes across it's long, strong torso, turning into bands on it's long, bushy tail. The family that this species belongs to has also evolved from the Brush tailed possum, the group is known as the Carnophalangeridae, the family also has produced bear-like and hyaena-like possums.

-

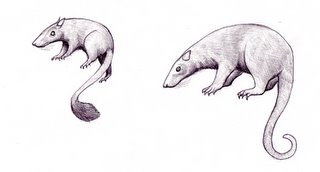

Down on the forest floor, amongst the lower branches of the olive thickets, a cat sized rodent snuffles and roots for tubers and seeds, aswell as insects and worms. The hograt (Suinorattus blandi), with a large, shovel like nose, is the only truly remarkable rodent in the woods. Red backed, yellow bellied fruit rats (Frugorattus foetidus), are omnivores that can be found in any level of the forest, and are the most common of the forest's rodents. The forest rodents breed frequently, and mate almost every day.

A huge, red and white form, ambles into view, somewhere between a bear and a guinea-pig in appearance, this creatire is actually a giant wombat. The Panda-wombat (Ailuropodovombatus giganteus), feeds entirely on the thick groves of ferns that make up the majority of the low undergrowth, aswell as fern stems, and it also does eat fruit. The size of a brown bear, and just as angry, with patches of red fur around the eyes, white cheeks, a mostly red-brown body, with white patches on the back. It reaces out and grabs with it's large-clawed paws a huge clump of fern and sits up with it to dine.

As some fruit rats run around it's feet, the panda wombat bellows in anger as it sees a small, slinking predator. The Marsuipial cat (Phascolofelis nanus) the size of a common tabby, and closely resembling a cat, is just as fond of rodents. It pounces on one unlucky rat as the old Panda-wombat ambles away. Descended from marsuipial mice, Marsuipial cats can be found in many climates and habitats in meganesia, where they vary by colour and fur thickness.

The back and tail of a strange, dinosaur-like beast, one and a half metres tall at the shoulders, bristling with horny spikes and scales, wanders in the wake of the huge wombat. No reptile, but a huge, root-and-tuber-eating echidna, the Stegochidna (Stegoglossus armatus), digs with it's gargantuan foreclaws for the remains of the wombat's feast below the ground. Walking on it's knuckles, and having a huge, roman-nosed head, it grinds the tubers beween horny plates in it's jaws and on it's tongue. It also greedily eats grubs and worms, as well as fallen fruit. It's skin is sparesly furred with short, black fuzz, and it's skin is two-centimetre-thick, horny leather. The spines are long and sharp along the back, being bright red, becoming orange plates on the hips and tail.

Long legs and a long tail lope by as a Gerenuk-wallaby (Neoprotemnodon gracilis), a descendant of the black wallaby, browses quietly. Though it's colour is much like that of it's ancestor, the physiology has changed. It has a long face, long ears, upturned nose, and powerfull snipping incisors and chewing molars set in a deep jaw, and a long tongue to aid in gathering the leaves it eats. It's neck and torso are extremely long and slender, as are it's arms, all to aid it in it's browsing. It's legs and feet are extended and danity, with the help of it's tail this allows it to reach up to three meeters into the trees, but when it is standing normally, it is around 2 metres tall. On the plains, such roles are filled by camels, but as bushy trees grew taller in the southern woods, some wallabies followed this food source before the camels could migrate south. The result is the numerous species of tree dwelling and tall browsing wallabies.

Suddenly the forest is pierced with a terrible screeching, the Gerenuk wallaby bounds off with the amazing speed typical of it's species. Startled, a flock of tiny, gold Quagga finches (Nanospizza aureus), descendants of the holocene zebra finch, fly by. Once grassland dwellers, some of their stock evolved into flyers of the lower levels, eating insects and fruit off the forest floor. The once short bill of the grass-dwelling finches has now become an acute, long, tong like apparatus for gathering forest fare.

The source of the screeching is revealed when a greivously injured spotted false moa (Nanodromauius agilis), stumbles into the dappled light. Unlike it's larger cousins it is only one point seven metres high, living on herbaceous plants and leaves, much like the emu, it's ancestor. With black feathers, spotted with white patches, it also feeds on fruit and small animals. It can run fast, about seventy kilometres maximum, when healthy, but this bird's life is about to be cut short.

It's persuers come into view, alsatian sized, long legged, with dappled black spots on a fawn or red-brown background, they initially look like some strange pack of dogs. They are Quollupes (Lupequoll socialis), wolf quolls, the forest's answer to pack hunting canids. They tear the poor bird to shreds, and gorge on it's meat and entrails, with independantly evolved carnassial shearing teeth, bone crushing back molars, and long canines, the once timid quoll has left a bloodthirsty legacy. The Quollupes are also found in open areas, with different species across the continent.

Once the quoll-dogs move away, the carcass, what's left of it, starts to decompose, food for microbes and insects. As large carrion beetles swarm over the blooody shreds, another, tinier pack hunter comes into view. Running bats (Cursochiropteryx diabolis), only the size of a mouse, scramble onto the carcass and make short work of the beetles. With long, strong legs, and short, sharp claws, this bat, agile in the air and on the ground, can run extemely fast when the need arises. It still flies, but only when startled or escaping a predator, or migrating to richer feeding grounds. Being blotchily patterned to look like pices of leaf litter, so to avoid prowling and low flying predators, they sleep in communal burrows amid tree roots. They are descendants of the equally tiny insectivorous bats that hawk for insects on holocene nights over Adelaide, Melbourne, and Sydney.

The near extintion of predatory birds like falcons has also driven some bats to hawk through the undergrowth by day. The Hawking razor-bat (Smilochiropteryx falconoides), is one such creature. With broad, manouverable, fifthy centmetre wide wings, it can fly, near soundlessly, through the undergrowth, it's chequered grey pelt blending with the forest shadows. It's feet have curved talons, and it's mouth is filled with long, razor sharp fangs, it can grab a rodent, lizard or bird while still on the wing. It's face has large, dish like ears, large keen eyes and a crinkled snout. It's sense of smell is keen also, it can scent the small animals if the forest is too overgrown.

Another coniseurr of insects, worms, small vertebrates and also fruit is the mauruipial racoon (Omnivorantechinus medius). The size of a racoon or coati, it is descended from the Antechinus, which beat other small creatures to the role of generalised omnivory over much of Australia's forest floor. The bandicoots that used to fill such niches were hunted to extinction by feral cats early in the neocene, before meganesia's carnivorans went extinct. It's colouration is a dappled and banded brown, which is fawn in the females and auburn in males. It's head is flat, it's teeth broad, and it's canines are large so it can deal with large insects and small vertebrates as well as fruit and seeds.

The forest floor's prime insect eater is the ground echidna (Geoglossus spinatus), which can be found across meganesia. Much like it's ancestor, this fifty centimeter, five kilogram, spiny monotreme eats mostly small insects, namely ants and termites. It is brown-grey, with yellow horny spines amongst thick fur, it has a much bigger spur than it's ancestor, the echidna. The echidna's spur was once a small, atrophied stump, without a sheath, but as they evolved during the neocene, they retained a sheathed spur into adulthood, and it soon became larger. The spur is now bright orange, long and very venomous, it is needed all the more in a forest full of marsuipial predators. As extra detterant for predators, it has large spines on it's tail, which stick up like a cluster of small knives.

Inumerable invertebrates, worms, beetles, isopods, swarm amongst the soil, processing the dead leaves, fruit and gauno. But they mostly go unseen, or become food for larger beasts. One, The Gargantual burrowing cockroach (Titanoblatta hoplitochelys), is far more noticeable. A giant, wingless, burrowing cockroach, fifteen to twenty centimetres long, it is descended from the bush burrowing cockroach of the holocene, but coloured metallic jet black. It feeds mostly on dead leaves and fallen fruit.

The woodland dung-beetles (Australoscarabaeus sp) are descended from the dung beetles that were introduced to controll cattle dung during pastoral times in the holocene. These descendants are the sewage cleanup crew of the forest floor.

Tim